History of the Modern Bow

History of the Modern Bow

The bow has evolved to produce more sound with higher tension strings

The bow currently used by thousands of classical, jazz, folk, country, bluegrass and rock players is a design which has existed for over two hundred years. During the mid- to late-18th century, radical changes were made to the violin bow which corresponded to the changes in music and the violins themselves. Prior to this time, the “baroque” bows were relatively simple -- some had screw devices to tighten the hair, and they were carved straight so that under tension, they had a convex bend in the stick. They were made from various European hardwoods, and with the exception of the screw, they were made with no metal parts at all.

“Exactly who was most responsible for first implementing the changes to produce the ‘modern’ bow is a fact lost to history”

But music was changing rapidly in the time of Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven -- it was becoming more popular in large concert halls and opera theaters, and was no longer the exclusive domain of churches, courts and royal chambers. In these larger venues, stringed instruments were called upon to produce more volume. As a result, the instruments evolved, and were modified so that they could use strings with a higher tension, and produce more sound. But the bows themselves were not adequate for producing the volume that the instruments were by then capable of.

Exactly who was most responsible for first implementing the changes to produce the “modern” bow is a fact lost to history, and might never be known. Many European craftsman in the late 18th century were illiterate, and there is scant written evidence of their work. However, most experts agree that it was a number of players and makers working collaboratively in England, France and Germany who were able to make several very important changes. French bow makers are generally credited with most of these changes, and foremost among the innovations was to make the stick out of a Brazilian hardwood. This wood, which became known as “pernambuco,” came from the Brazilian province named Pernambuco, and the port city of the same name, now known as Recife. The French had colonies in this area, and the wood was originally exported back to Europe for use in the fabric and dye industry.

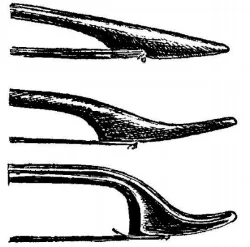

The properties of this pernambuco wood were uniquely well-suited for the new bows -- it was very dense, and had the right combination of flexibility and stiffness. Equally important, the wood could be bent by using heat, and if done carefully, would not break during this process. This allowed for another important innovation: the concave form of the stick. For the first time, the sticks were made with a curve towards the hair, which the hair could tighten against. This produced more tension on the hair, a stronger bow, and the result was that the player could coax more sound from the instrument using a bow of this design.

After that, there were a number of other less dramatic but nonetheless important refinements in the bowmaking process. Most of them involved the addition of several metal fittings to the part of the bow that moves back and forth to adjust the hair tension, known in America as the “frog.” A metal ferrule was added to the frog where the hair enters it, allowing the horsehair to be spread into a thinner, flatter ribbon. The top of the frog was commonly fitted with a thin metal reinforcement, and a metal heelplate. The adjusting button itself also was made with metal, thereby making it more durable than the previous baroque types, which were usually hardwood or ivory. At the opposite end of the stick, the tip was also reinforced with an ivory or metal “headplate,” which made the stick less susceptible to damage and more sturdy when the hair was removed and replaced.

Most of these improvements were commonly embraced by the majority of bowmakers in Europe by the turn of the 19th century. By this time, bow making had truly become an extremely fine art unto itself, attracting some of the most skilled craftsmen. Besides the beautiful pernambuco wood, these makers also used ebony, ivory and tortoiseshell for the frogs, and mounted them with nickel, sterling silver and gold fittings. The most expensive materials were reserved for the maker’s best efforts with the best pernambuco. Authentic examples by these early masters now have enormous value to both player and collector, and can cost many tens of thousands of dollars.

Since the early 1800’s, very few changes have occurred in bowmaking and the bows used today are virtually identical in form and function. The art of bowmaking has experienced something of a resurgence in the last half-century, and many fine bow makers thrive in numerous parts of the globe. It should be noted, though, that contemporary bow makers restrict their use of materials from endangered species, particularly the afformentioned ivory and tortoiseshell. Modern bow makers and bowmaking shops have access to more sophisticated machine tools to help them craft certain parts of the bow; but an individual maker will still do the majority of the work entirely by hand. The result is a bow which will inevitably exhibit individual character in its elegant form.